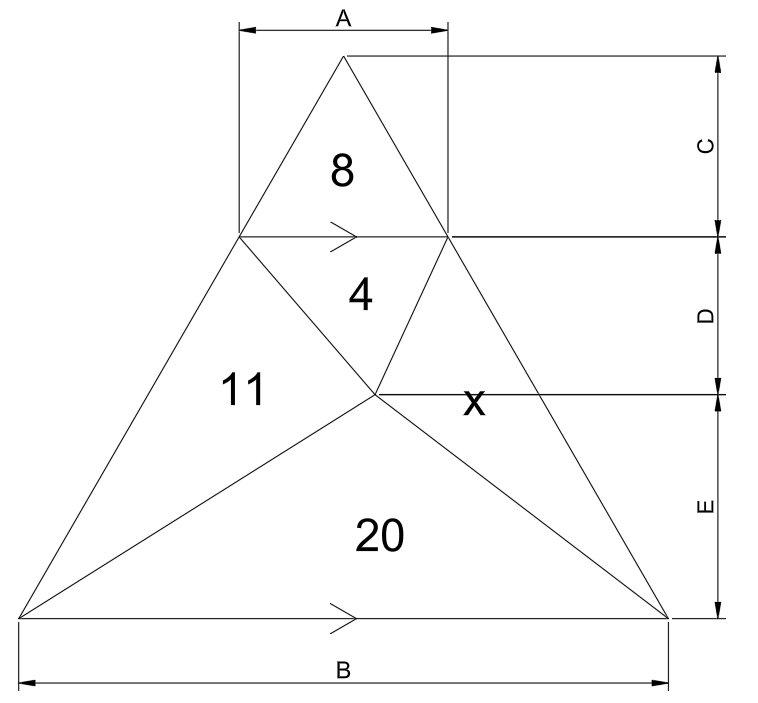

The area of the third region is 4.

I’m going to show that this is the case a little back-to-front, by presupposing that the overall area of the nonagon is 9, and then proving that that is in fact the case.

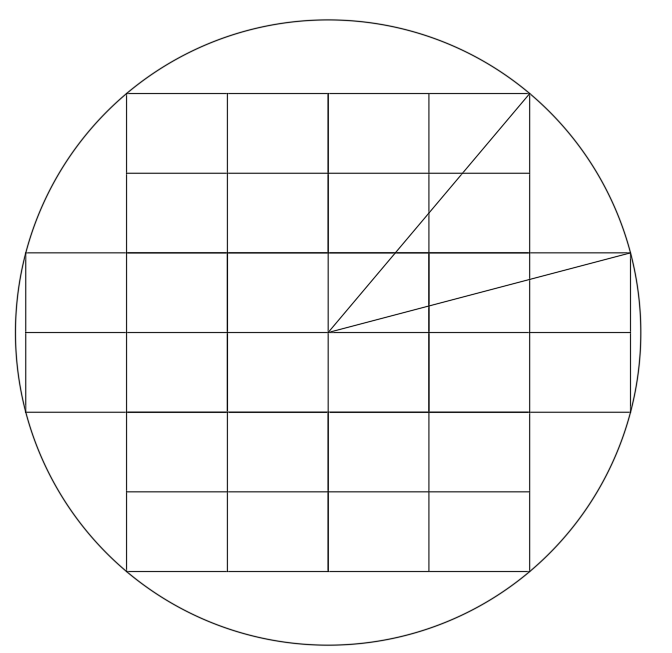

First of all I hope it’s evident that there is exactly one size of nonagon for which, if you form a triangle of area 2 using one side as the base and a vertex somewhere opposite, that the region to the left has area 3. That being the case, if we find a size of nonagon that works, that is THE solution.

So next I’m going to claim that the overall area is 9 (and therefore the missing are is 4) and show that that does indeed work.

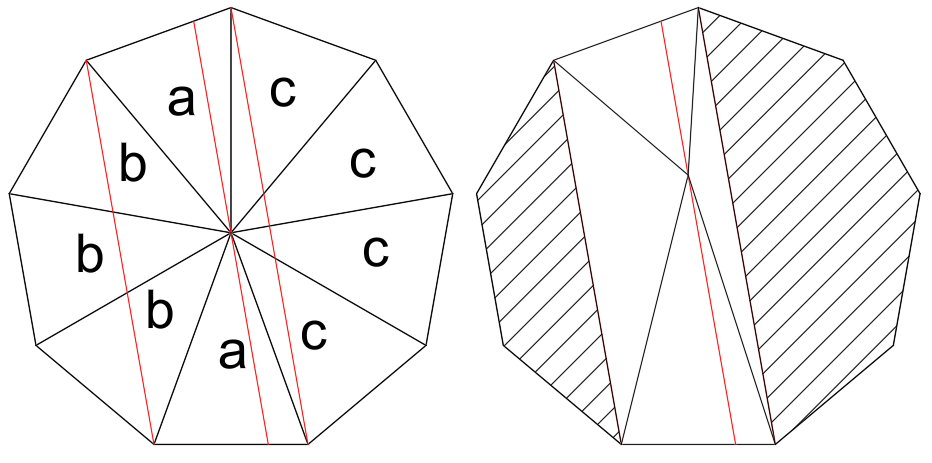

Drawing lines from each of the vertices to a point in the exact centre will divide the nonagon into 9 equal regions of area 1, therefore the combined area of the a regions is 2, of the b regions is 3, and of the c regions is 4.

The red lines are all parallel – the left and right ones are parallel because of the inherent symmetry of a regular nonagon, and I have defined the middle red line to be parallel to the others and passing through the centre of the nonagon.

In the second figure we can see that if we moved the point that all of the vertices of the nonagon were connected to (the hub if you will), but ensured it stayed on this middle red line, that the combined area of the b regions would remain 3. This is because the left shaded region is unaffected by the change, and the other part of the b region is a triangle with a fixed base and a fixed altitude.

The exact same rationale applies to the c region, which will remain 4 regardless of where on the middle red line the hub is.

Finally the a region will remain area 2, because the overall area of 9 is unaffected, and the a region includes everything not in either the b or c regions. This being the case we can let the hub move all the way to the top edge of the nonagon, meaning that the a region becomes a single triangle, and the b and c regions remain 3 and 4 respectively.